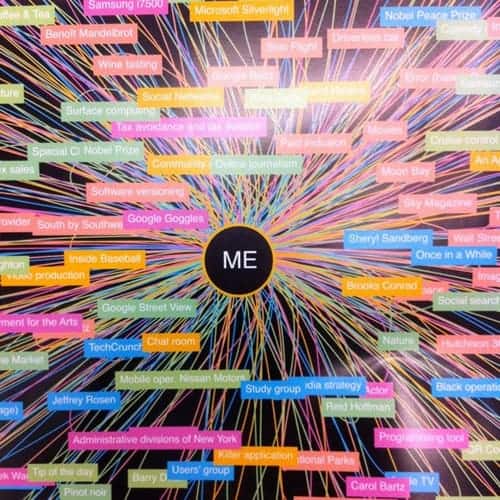

Above: Robert Scoble’s Interest Graph, via Gravity.com

The Interest Graph vs The Knowledge Graph

originally published in MediaPost’s Social Media Insider

What’s more valuable: your interests or what you want to know? The difference between the Interest Graph and the Knowledge Graph will shape the direction of two major technology companies in the years ahead, and this will in turn impact billions of dollars of marketing spending.

Google just wrapped its annual I/O conference, and a key theme this year was the Knowledge Graph. Google initially introduced the concept in May with a fairly popular video. At the time, I was underwhelmed, starting with the opening lines from Product Management Director Jack Menzel: “Wouldn’t it be amazing if Google could understand the words that you use when you’re doing a search? Well, they aren’t just words. They refer to real things in the world.” You mean this isn’t the case already? Google better understand that when I’m searching for “Oreo cookie balls,” I’m not just entering a series of letters like a proverbial monkey on a typewriter, but I’m looking to either make or buy some real (and delicious) things made of cream cheese, melted chocolate, and Oreos.

Even if the Knowledge Graph is just a fancy word for making search results relevant, Google’s new version of its Android operating system will tap the Knowledge Graph for answers to “questions about traffic, sports scores, and general information,” according to Silicon Alley Insider’s I/O roundup. The Knowledge Graph, featuring a database of more than 500 million entries with more than 3.5 billion attributes collectively, may well be important for Google’s future. The I/O updates that should stick around the longest and have the greatest impact for Google tend to be the more technical updates, such as mass transit routes built into Android and the Compute Engine to run cloud computing for applications. It will have a harder time winning over users for its consumer products like Nexus Q (an Apple TV competitor), Nexus 7 (an iPad and Kindle Fire competitor), Google+ events (a Facebook competitor) and Chrome for iPhone and iPad (competing with the native Safari browser).

Now take a look at Twitter. It’s finally making headway in tapping into its Interest Graph. While the term seems to first appear in an academic blog post by Joel Foner in December 2009, the next references appear in April 2010. As John Battelle noted on his blog that month, “To me the most interesting concept Twitter introduced last week was how they planned on tuning their ad platform to something Twitter COO Dick Costolo, in an interview with me on stage, called ‘the public interest graph.’ More likely than not Dick’s been talking about this for some time, but so far not many folks have picked it up. The first mentions of ‘public interest graph’ (as related to Twitter) first appear on Google April 15th – the day Dick mentions it. On stage, I was taken aback, because the concept struck me as pretty powerful.” Google doesn’t list any references to the “public interest graph” before 2010, and any broader “interest graph” references beyond Foner’s seem to discuss compound interest rather than social media. I first encountered the concept at an event at Twitter headquarters in June 2010, and when Costolo described it, I couldn’t wait for it to come to life.

The vision, as Costolo expressed it back in 2010, was that the Interest Graph would look at everyone a user follows and create a map of their interests. If you follow Chris Bosh and Dwyane Wade, it would assume you’re not just interested in basketball but the Miami Heat. It would pay attention to the content shared in tweets rather than brief descriptors in one’s biography. For instance, if you follow me at @dberkowitz, Twitter’s Interest Graph will (I hope) skip the snark and assume you’re more interested in marketing than serial killing.

Tapping the Interest Graph allows ads to become more relevant over time. If you never tweeted about the Heat but your Interest Graph indicated you were likely a fan, Twitter could in time allow Nike to advertise its new LeBron James sneakers to you and other probable Heat fans. Then – if you’re using a mobile device – Twitter could show you the store nearest you with them in stock. For some advertisers, this is what they’ve been dreaming of, especially if Twitter can reliably prove its relevance.

Google has one project in the works that could be as powerful in terms of predicting demand: Google Now. It will proactively deliver personalized results to Android users’ home screens based on their calendars, locations, searches, and other specific interests like sports teams and transportation schedules. Considered Google’s personal assistant, it’s designed to reduce the need for some searches entirely. It has a built-in ad model, but it faces several challenges: Users must opt in to the service, then must opt in to specific modules (or “cards”), it’s only for Android, and it will create the biggest digital privacy scare yet if it runs ads so relevant that users feel like they are being stalked. Other than that, it’s perfect.

Google should fare better with its Knowledge Graph — but again, that’s a way of saying its search results will stay relevant. Less exciting still for marketers is that Knowledge Graph results tend to occupy digital real estate previously reserved for ads. Twitter’s Interest Graph, meanwhile, was designed with advertisers in mind. The more targeted it gets, the more marketers will be interested.

No Comments

Leave a comment Cancel